Vanilla GANs

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have revolutionized the field of generative modeling, enabling the creation of highly realistic synthetic data. In this post, we’ll dive into the theory behind Vanilla GANs, introduced by Ian J. Goodfellow and his colleagues in the paper “Generative Adversarial Nets,” and explore their implementation in code using PyTorch.

The Concept of Adversarial Training

At the core of GANs lies the concept of adversarial training. The architecture comprises two neural networks: a generator (G) and a discriminator (D), engaged in a competitive game. The generator aims to create synthetic data that closely resembles real samples, while the discriminator tries to distinguish between genuine and generated data. During training, the networks are updated simultaneously, with the generator striving to improve its output and deceive the discriminator, and the discriminator enhancing its ability to differentiate between real and fake data.

Generator Network

The generator network takes random noise as input and generates synthetic data. It typically consists of linear layers as hidden layers and uses activation functions such as Leaky ReLU in the hidden layers and tanh in the output layer. The tanh activation function scales the output to be between -1 and 1, which has been found to perform well for the generator.

Here’s the code for the generator network:

class Generator_vanilla(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, latent_dim: int, hidden_dim: int, output_size: int):

super(Generator_vanilla, self).__init__()

# define hidden linear layers

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(latent_dim, hidden_dim)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim*2)

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim*2, hidden_dim*4)

# Apply Xavier initializer to the linear layers

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc1.weight)

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc2.weight)

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc3.weight)

# final fully-connected layer

self.fc4 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim*4, output_size)

# define the dropout

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(0.3)

# define the activation

self.activation = nn.LeakyReLU(0.2)

self.final_activation = nn.Tanh()

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = self.fc1(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = self.fc2(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = self.fc3(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.fc4(x)

x = self.final_activation(x)

return x

The generator consists of three hidden linear layers (self.fc1, self.fc2, self.fc3) with increasing dimensions. The Xavier initializer is applied to the weights of these linear layers to improve convergence. Dropout is used for regularization, and Leaky ReLU is used as the activation function in the hidden layers. The final layer (self.fc4) maps the output to the desired dimensions, and a tanh activation function is applied to scale the output to the range [-1, 1].

Discriminator Network

The discriminator network acts as a binary classifier, predicting whether the input data is real or generated. It also uses linear layers as hidden layers and applies activation functions such as Leaky ReLU and sigmoid. Leaky ReLU allows gradients to flow backwards through the layer unimpeded, while sigmoid is used in the final layer to produce a probability score between 0 and 1.

Here’s the code for the discriminator network:

class Discriminator_vanilla(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size: int, hidden_dim: int):

super(Discriminator_vanilla, self).__init__()

# define hidden linear layers

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_size, hidden_dim * 4)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim * 4, hidden_dim * 2)

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim * 2, hidden_dim)

# Apply Xavier initializer to the linear layers

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc1.weight)

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc2.weight)

init.xavier_uniform_(self.fc3.weight)

# define the final layer

self.fc4 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1)

# define the dropout

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(0.3)

# define the activation

self.activation = nn.LeakyReLU(0.2)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

# flatten image

x = x.view(-1, 28*28)

x = self.fc1(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = self.fc2(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = self.fc3(x)

x = self.activation(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

# we are using BCE with logits loss, so the last activation is not required

x = self.fc4(x)

return x

The discriminator consists of three hidden linear layers (self.fc1, self.fc2, self.fc3) with decreasing dimensions. Similar to the generator, the Xavier initializer is applied to the weights of these linear layers. Dropout is used for regularization, and Leaky ReLU is used as the activation function in the hidden layers. The final layer (self.fc4) produces a single output value, which represents the discriminator’s prediction. Since we are using binary cross-entropy with logits loss, no activation function is applied to the final layer.

GANs Loss Function

The loss function plays a crucial role in training GANs. For the discriminator, the total loss is the sum of the losses for real and fake images: d_loss = d_real_loss + d_fake_loss. We want the discriminator to output 1 for real images and 0 for fake images.

To achieve this, we use the nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss function, which combines a sigmoid activation function and binary cross-entropy loss. It’s important to note that the final output layer of the discriminator should not have any activation function applied to it.

Label smoothing is a technique used to help the discriminator generalize better. Instead of using a target label of 1.0 for real images, we slightly reduce it to 0.9. This encourages the discriminator to be less confident and produces more diverse and realistic samples.

For the generator, the goal is to fool the discriminator into classifying the generated images as real. The generator loss is calculated using flipped labels, where the target label for generated samples is set to 1.0 instead of 0.0.

Here’s the code for the loss functions:

# Calculate losses

def real_loss_vanilla(D_out, smooth=False):

# label smoothing

labels = torch.ones_like(D_out) * (0.9 if smooth else 1.0)

# numerically stable loss c

criterion = nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss()

# calculate loss

loss = criterion(D_out, labels)

return loss

def fake_loss_vanilla(D_out):

labels = torch.zeros_like(D_out) # fake labels = 0

criterion = nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss()

# calculate loss

loss = criterion(D_out, labels)

return loss

In the real_loss_vanilla function, we calculate the loss for real images. If label smoothing is enabled (smooth=True), we set the target labels to 0.9 instead of 1.0. We then use the nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss criterion to compute the binary cross-entropy loss between the discriminator’s output (D_out) and the target labels.

In the fake_loss_vanilla function, we calculate the loss for fake (generated) images. The target labels for fake images are set to 0. We again use the nn.BCEWithLogitsLoss criterion to compute the loss between the discriminator’s output and the target labels.

Training Vanilla GANs

Training Vanilla GANs involves alternating between updating the discriminator and the generator. Here’s the code for the training loop and helper functions:

# helper function for viewing a list of passed-in sample images

def view_samples(epoch, samples):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(figsize=(14, 4), nrows=2, ncols=8, sharey=True, sharex=True)

for ax, img in zip(axes.flatten(), samples[epoch]):

img = img.detach().cpu() # Move tensor to CPU

ax.xaxis.set_visible(False)

ax.yaxis.set_visible(False)

im = ax.imshow(img.reshape((28, 28)).cpu().numpy(), cmap='Greys_r') # Convert to NumPy array

plt.show()

def training(model_G, model_D, z_size, g_optimizer, d_optimizer, real_loss, fake_loss, g_scheduler, d_scheduler, nb_epochs, data_loader, device='cuda'):

# training hyperparams

num_epochs = nb_epochs

# keep track of loss and generated, "fake" samples

samples = []

losses = []

print_every = 100

# Get some fixed data for sampling. These are images that are held

# constant throughout training, and allow us to inspect the model's performance

sample_size = 16

fixed_z = torch.randn((sample_size, z_size)).to(device)

# train the network

model_D.train()

model_G.train()

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for batch_i, (real_images, _) in enumerate(data_loader):

real_images = real_images.to(device)

batch_size = real_images.size(0)

## Important rescaling step from [0,1) to [-1, 1)##

real_images = real_images * 2 - 1

# ============================================

# TRAIN THE DISCRIMINATOR

# ============================================

d_optimizer.zero_grad()

# 1. Train with real images

# Compute the discriminator losses on real images

# smooth the real labels

D_real = model_D(real_images)

d_real_loss = real_loss(D_real, smooth=True)

# 2. Train with fake images

# Generate fake images

# gradients don't have to flow during this step

with torch.no_grad():

z = torch.randn((batch_size, z_size)).to(device)

fake_images = model_G(z)

# Compute the discriminator losses on fake images

D_fake = model_D(fake_images)

d_fake_loss = fake_loss(D_fake)

# add up loss and perform backprop

d_loss = d_real_loss + d_fake_loss

d_loss.backward()

d_optimizer.step()

# =========================================

# TRAIN THE GENERATOR

# =========================================

g_optimizer.zero_grad()

# 1. Train with fake images and flipped labels

# Generate fake images

z = torch.randn((batch_size, z_size)).to(device)

fake_images = model_G(z)

# Compute the discriminator losses on fake images

# using flipped labels!

D_fake = model_D(fake_images)

g_loss = real_loss(D_fake) # use real loss to flip labels

# perform backprop

g_loss.backward()

g_optimizer.step()

# Print some loss stats

if batch_i % print_every == 0:

# print discriminator and generator loss

time = str(datetime.now()).split('.')[0]

print(f'{time} | Epoch [{epoch+1}/{num_epochs}] | Batch {batch_i}/{len(data_loader)} | d_loss: {d_loss.item():.4f} | g_loss: {g_loss.item():.4f}')

## AFTER EACH EPOCH##

# append discriminator loss and generator loss

losses.append((d_loss.item(), g_loss.item()))

# Call the scheduler after the optimizer.step()

g_scheduler.step()

d_scheduler.step()

# generate and save sample, fake images

model_G.eval() # eval mode for generating samples

samples_z = model_G(fixed_z)

samples.append(samples_z)

# Assuming view_samples is a function to visualize generated samples

view_samples(-1, samples)

model_G.train() # back to train mode

# Save training generator samples

with open('train_samples.pkl', 'wb') as f:

pkl.dump(samples, f)

return losses, samples

The view_samples function is a helper function for visualizing a list of generated sample images. It takes the epoch number and the list of samples and plots the samples in a grid using Matplotlib.

The training function is the main training loop for the Vanilla GAN. It takes the generator model (model_G), discriminator model (model_D), latent space size (z_size), optimizers (g_optimizer, d_optimizer), loss functions (real_loss, fake_loss), learning rate schedulers (g_scheduler, d_scheduler), number of epochs (nb_epochs), data loader (data_loader), and device (device) as inputs.

Inside the training loop, the following steps are performed:

- Train the discriminator:

- Zero the gradients of the discriminator optimizer.

- Compute the discriminator loss on real images using

real_lossand label smoothing. - Generate fake images using the generator with random noise.

- Compute the discriminator loss on fake images using

fake_loss. - Sum up the real and fake losses and perform backpropagation and optimization step.

- Train the generator:

- Zero the gradients of the generator optimizer.

- Generate fake images using the generator with random noise.

- Compute the discriminator loss on fake images using flipped labels (

real_loss). - Perform backpropagation and optimization step.

- Print loss statistics and save generated samples:

- Print the discriminator and generator losses at regular intervals.

- Append the losses to the

losseslist. - After each epoch, generate and save sample fake images using fixed noise (

fixed_z). - Visualize the generated samples using the

view_samplesfunction.

- Update learning rate schedulers:

- Call the learning rate schedulers (

g_scheduler.step(),d_scheduler.step()) after each epoch.

- Call the learning rate schedulers (

- Save the generated samples:

- After training, save the generated samples to a file using pickle.

The training function returns the losses and generated samples for further analysis and visualization.

Case Study: Generating Handwritten Digits with Vanilla GAN

In this case study, we will demonstrate how to use the Vanilla GAN architecture to generate handwritten digits using the MNIST dataset. We’ll go through the code step by step, explaining the hyperparameters, optimizers, and schedulers used in the training process.

Loading the MNIST Dataset

First, we need to load the MNIST dataset and prepare the data loader. We’ll use the torchvision library to download and transform the dataset.

import torch

from torchvision import datasets

import torchvision.transforms as transforms

# number of subprocesses to use for data loading

num_workers = 4

# how many samples per batch to load

batch_size = 128

# convert data to torch.FloatTensor

transform = transforms.ToTensor()

# get the training datasets

train_data = datasets.MNIST(root='data', train=True,

download=True,

transform=transform)

# prepare data loader

train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(train_data,

batch_size=batch_size,

num_workers=num_workers)

We set the batch_size to 128, which means the model will process 128 images per batch during training. The num_workers parameter determines the number of subprocesses used for data loading, which can help speed up the data retrieval process.

Defining Hyperparameters

Next, we define the hyperparameters for the discriminator and generator networks.

# Discriminator hyperparams

# Size of input image to discriminator (28*28)

input_size = 784

# Size of last hidden layer in the discriminator

d_hidden_size = 256

# Generator hyperparams

# Size of latent vector to give to generator

z_size = 100

# Size of discriminator output (generated image)

g_output_size = 784

# Size of first hidden layer in the generator

g_hidden_size = 32

The input_size represents the size of the input image to the discriminator, which is 28x28 pixels (784 when flattened). The d_hidden_size determines the size of the last hidden layer in the discriminator.

For the generator, z_size represents the size of the latent vector (random noise) that will be used as input. The g_output_size is set to 784, matching the size of the generated image. The g_hidden_size determines the size of the first hidden layer in the generator.

Creating the Models

We create instances of the Discriminator_vanilla and Generator_vanilla classes, which define the architectures of the discriminator and generator networks, respectively.

D = Discriminator_vanilla(input_size, d_hidden_size)

G = Generator_vanilla(z_size, g_hidden_size, g_output_size)

device = torch.device("cuda:0" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu")

model_D = D.to(device)

model_G = G.to(device)

We move the models to the appropriate device (GPU if available, otherwise CPU) using model_D.to(device) and model_G.to(device).

Defining Optimizers and Schedulers

We define the optimizers and learning rate schedulers for the discriminator and generator.

import torch.optim as optim

from torch.optim.lr_scheduler import MultiStepLR

# Optimizers

lr_G = 0.001

lr_D = 0.0001

num_epochs = 100

# Create optimizers for the discriminator and generator

d_optimizer = optim.Adam(model_D.parameters(), lr=lr_D, betas=(0.5, 0.999))

g_optimizer = optim.Adam(model_G.parameters(), lr=lr_G, betas=(0.5, 0.999))

# Learning rate scheduler

# Set the list of milestones when you want to adjust the learning rate

d_milestones = [50]

g_milestones = [20, 50, 80]

d_scheduler = MultiStepLR(d_optimizer, milestones=d_milestones, gamma=0.1)

g_scheduler = MultiStepLR(g_optimizer, milestones=g_milestones, gamma=0.5)

We use the Adam optimizer for both the discriminator and generator, with different learning rates (lr_D and lr_G). The betas parameter controls the decay rates for the first and second moment estimates.

The choice of using different learning rates for the generator and discriminator is supported by both theoretical and empirical evidence. The idea is to give the generator a higher learning rate (lr_G = 0.001) compared to the discriminator (lr_D = 0.0001) to allow it to adapt more quickly and keep up with the discriminator’s progress. This approach can help prevent the discriminator from becoming too dominant and overpowering the generator, promoting more stable and effective training dynamics.

Several papers, such as “Improved Techniques for Training GANs” by Salimans et al. (2016) and “Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?” by Mescheder et al. (2018), discuss the benefits of using different learning rates for the generator and discriminator. They provide empirical results and theoretical analysis supporting this approach, showing that it can lead to improved sample quality and more stable training.

However, it’s important to note that the optimal learning rates and the ratio between them may vary depending on the specific GAN architecture, dataset, and problem domain. Experimentation and tuning are often required to find the best learning rate settings for a particular GAN application.

The learning rate schedulers (MultiStepLR) are used to adjust the learning rates at specified milestones during training. For the discriminator, the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.1 at epoch 50. For the generator, the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.5 at epochs 20, 50, and 80.

Training the Vanilla GAN

We train the Vanilla GAN using the training function, passing in the necessary parameters.

losses, samples = training(model_G, model_D, z_size, g_optimizer, d_optimizer,

real_loss_vanilla, fake_loss_vanilla, g_scheduler,

d_scheduler, num_epochs, train_loader, device='cuda')

The training function takes the following parameters:

model_G: The generator modelmodel_D: The discriminator modelz_size: The size of the latent vectorg_optimizer: The optimizer for the generatord_optimizer: The optimizer for the discriminatorreal_loss_vanilla: The loss function for real imagesfake_loss_vanilla: The loss function for fake imagesg_scheduler: The learning rate scheduler for the generatord_scheduler: The learning rate scheduler for the discriminatornum_epochs: The number of training epochstrain_loader: The data loader for the training datasetdevice: The device to run the training on (GPU or CPU)

During training, the generator and discriminator are updated alternately. The generator learns to generate images that can fool the discriminator, while the discriminator learns to distinguish between real and generated images.

Analyzing the Results

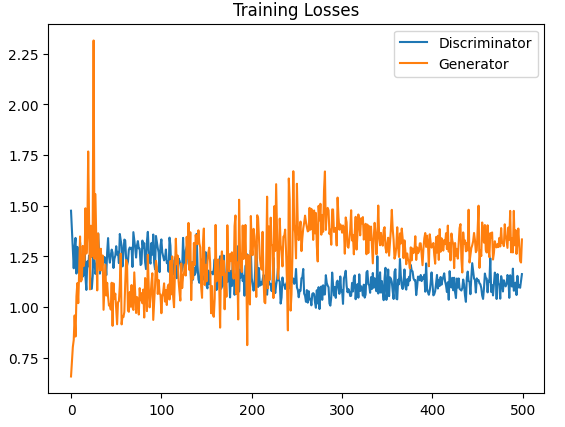

After training, we can analyze the results based on the training losses and the generated images.

The training losses for the discriminator and generator show the competitive nature of the GAN training process. The fluctuations in the losses indicate that the discriminator and generator are constantly trying to outperform each other. As training progresses, the losses tend to stabilize, suggesting that the model is reaching a point of convergence. The stabilization of the losses towards the end of training indicates that the generator has learned to generate images that can effectively fool the discriminator, while the discriminator has learned to distinguish between real and generated images with high accuracy.

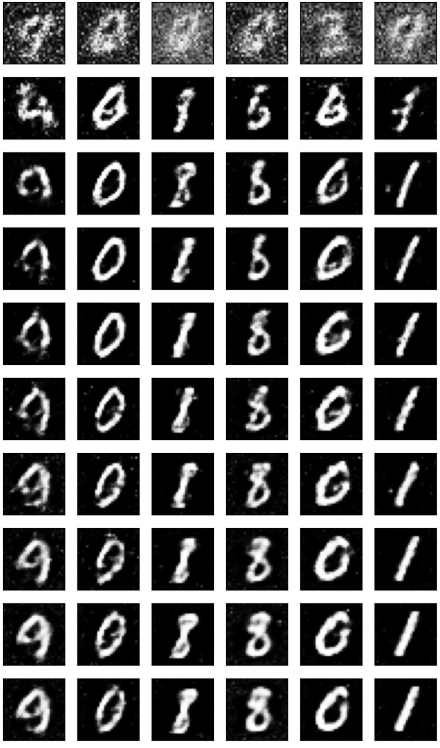

The image above shows the progression of generated handwritten digits by the Vanilla GAN every 10 epochs, from epoch 10 to epoch 100. Each row represents a specific epoch, showcasing the quality and diversity of the generated images at that point in the training process.

Epoch 10 (First Row): In the first row, corresponding to epoch 10, we can observe that the generated digits are starting to take shape, but they are still somewhat blurry and lack fine details. The generator is in the early stages of learning to capture the basic structure and patterns of the handwritten digits.

Epoch 20 (Second Row): Moving to the second row (epoch 20), we can see that the generated digits have become clearer and more recognizable. The generator has learned to produce images that resemble handwritten digits more closely, although some imperfections and variations are still present.

Epoch 30 (Third Row): By epoch 30, the generated digits have further improved in terms of clarity and consistency. The generator has captured more intricate details and styles of handwriting, resulting in more convincing and diverse samples.

Epoch 40 to Epoch 90: As we progress through epochs 40 to 90, the generated digits continue to refine and exhibit increasing quality and realism. The generator learns to generate images with finer details, smoother strokes, and better overall structure. The diversity of the generated samples also improves, showcasing various styles and variations of handwritten digits.

Epoch 100 (Last Row): In the final row, representing epoch 100, the generated digits have reached a high level of quality and realism. The generator has learned to produce handwritten digits that closely resemble those from the MNIST dataset. The digits are clear, well-formed, and exhibit a wide range of styles and variations.

Overall, the progression of generated images every 10 epochs demonstrates the gradual improvement of the Vanilla GAN’s ability to generate realistic handwritten digits. The generator learns to capture the underlying patterns, styles, and variations present in the MNIST dataset, resulting in increasingly convincing and diverse samples as the training progresses.

Tips and Tricks

- Experiment with different architectures: While the Vanilla GAN provides a good starting point, don’t hesitate to experiment with different architectures for the generator and discriminator. Try adding more layers, using different activation functions, or incorporating techniques like batch normalization to improve the quality and stability of the generated images.

- Adjust hyperparameters: The hyperparameters used in this case study, such as learning rates, batch size, and latent vector size, are just a starting point. Experiment with different values to find the optimal settings for your specific problem. Keep in mind that the ideal hyperparameters may vary depending on the dataset and the complexity of the images you’re trying to generate.

- Monitor training progress: Regularly monitor the training progress by keeping track of the generator and discriminator losses. If the losses are not converging or if one model is overpowering the other, it may indicate instability in the training process. Adjust the learning rates, architectures, or hyperparameters accordingly to achieve more stable training.

- Use data augmentation: Data augmentation techniques, such as random flips, rotations, or scaling, can help increase the diversity and robustness of the training data. By applying these transformations to the real images during training, you can improve the generalization ability of the GAN and prevent overfitting.

- Experiment with different loss functions: While binary cross-entropy loss is commonly used in Vanilla GANs, there are other loss functions worth exploring. For example, the Wasserstein loss has been shown to improve training stability and generate higher-quality images in some cases. Don’t hesitate to experiment with different loss functions to see if they yield better results for your specific task.

- Regularization techniques: Applying regularization techniques, such as L1 or L2 regularization, to the weights of the generator and discriminator can help prevent overfitting and improve the generalization ability of the models. Regularization encourages the models to learn more robust and meaningful features, leading to better quality generated images.

- Patience and iterative refinement: Training GANs can be a time-consuming and iterative process. Be patient and prepared to experiment with different settings, architectures, and techniques. It’s common to go through multiple iterations of training, evaluating the results, and making adjustments based on the observations. Gradually refine your models and hyperparameters until you achieve satisfactory results.

Conclusion

In this post, we explored the concept of Vanilla GANs and demonstrated their application in generating handwritten digits using the MNIST dataset. We walked through the process of loading the dataset, defining the generator and discriminator models, setting up the optimizers and schedulers, and training the GAN.

The case study showcased the ability of Vanilla GANs to generate realistic handwritten digits after training for a sufficient number of epochs. The generated images exhibited clear and recognizable digits, capturing the essential characteristics of the MNIST dataset.

However, it’s important to acknowledge that generating perfect images with fine details and no artifacts is still a challenge with Vanilla GANs. The generated images may sometimes lack sharpness, contain slight distortions, or have missing parts. These limitations can be addressed by exploring more advanced GAN architectures, such as Deep Convolutional GANs (DCGANs) or Progressive Growing of GANs (ProGANs), which have shown promising results in generating high-quality images.

Despite the limitations, Vanilla GANs provide a solid foundation for understanding the core concepts of adversarial training and serve as a stepping stone towards more sophisticated GAN models. By experimenting with different architectures, loss functions, regularization techniques, and hyperparameters, one can further improve the quality and diversity of the generated images.

GANs have opened up exciting possibilities in various domains, including image synthesis, style transfer, data augmentation, and more. The case study presented in this post is just a glimpse into the vast potential of GANs. As you continue to explore and experiment with GANs, keep an open mind, be creative, and don’t hesitate to try out new ideas and techniques.

Remember, the key to success with GANs is patience, experimentation, and continuous learning. With dedication and practice, you can harness the power of GANs to generate impressive and realistic images in your chosen domain.

References:

- Goodfellow, I. J., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., … & Bengio, Y. (2014). “Generative Adversarial Nets.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.2661. Link

- Salimans, T., Goodfellow, I., Zaremba, W., Cheung, V., Radford, A., & Chen, X. (2016). “Improved Techniques for Training GANs.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), 29, 2234-2242. Link

- Mescheder, L., Geiger, A., & Nowozin, S. (2018). “Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?” In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 3478-3487. PMLR. Link